The Pirates of the Caribbean have gotten all of the glory in American entertainment. Parents sit around theme park pools, telling tales to their children about Blackbeard and Kidd while sipping Captain Morgan. Our popular culture glamorizes the stories of these pirates close to home, as though they were the most fearsome and noteworthy the world has seen. Maybe we are products of a Disney era, but somehow little has been said about other places and times that would make our skin crawl. The pirates of the Western Hemisphere learned their trade from their brothers in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast corsairs.

Many of us have gone to Europe (or thought about it), dreaming of those incredible towns on the coast. The pictures are beautiful. This is a large part of the attraction of the Mediterranean countries for us.

In our dreams, we love to think about tripping down ancient cobblestone streets to the beach where we can lay on the sand and soak in the sun. Maybe order a limoncello or two. Later, we walk up to a restaurant overlooking the bay to order fish, true Italian pizza and ravioli. Life at its best! What we don’t know is that these coastal towns were constantly raided by pirates just a few hundred years ago. Its men, women and children were dragged away screaming in the night and put on ships. In the blink of an eye, they found themselves in slave markets in North Africa, then trafficked who knows where.

For a good 250 years between the 16th and 19th centuries, people were afraid to live on the coasts of the Mediterranean, should they and their children be captured and forced into slavery. Over a million Europeans were captured and enslaved during this time.

Piracy in the Mediterranean was much more organized and had a larger impact on the economy than most of us realize. Their reach was incredible. The pirates in this region were called “corsairs” (a word derived from corso, which meant to run or chase). Packs of corsairs would work together on far-reaching excursions. They pillaged towns, not only in the Mediterranean, but also up the coast of France to England, Ireland, and even Iceland. They once sacked a town in Ireland called Baltimore and took everyone as slaves except for a few who escaped into the nearby caves. A ghost town was formed overnight.

Corsair captains became admirals, and they were highly respected in the African cities. They could hold powerful positions in local governments. At its peak, piracy in the city of Algiers accounted for 25% of the workforce. The money was so good that many skilled Europeans would migrate to North Africa and convert to Islam, or do whatever they had to, so they could get in on the bounty.

Slave markets dotted the Barbary coastline like chickenpox. This was the big money item. Slaves sold for high prices, but even more lucrative was the ransoming of slaves. At the height of this plague, many countries in Europe had funds that were reserved for paying ransoms.

For the pirate-thriving hives on the African coast, the sugar high would not last. Europeans were pissed off that their loved ones were being stolen from their shores by barbarians. The American government was paying 20% of its annual budget on “tributes” so ships doing business in the Mediterranean could pass through it unmolested, and yet they were still getting molested. Enough was enough.

Routing the Barbary Hives

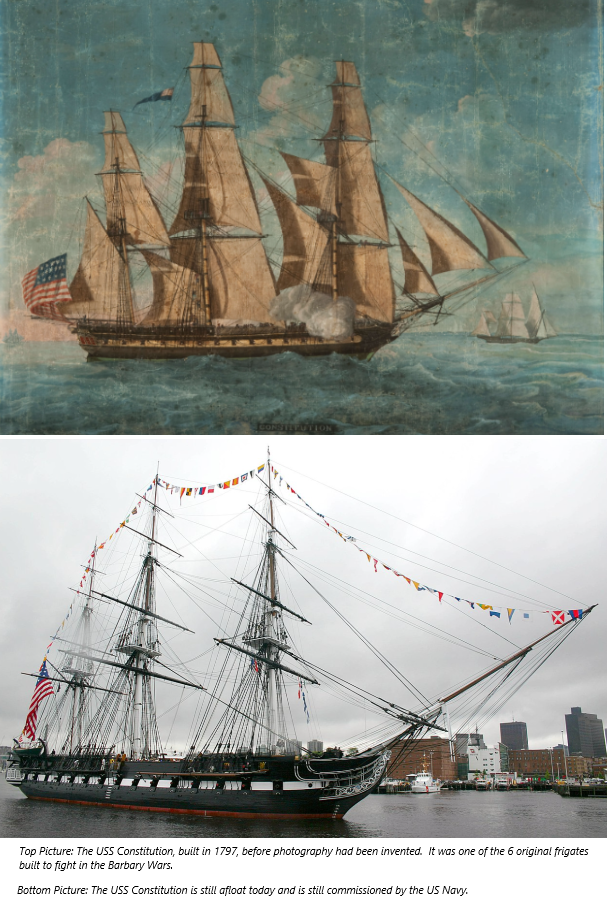

Here we enter an interesting historic chapter for America. Our first war as an independent nation was against these Islamic terrorists. It was the reason for the creation of our Navy and Marine Corps. George Washington urged Congress to set up its first Navy for the purpose of taking back control from the North African marauders. In the first-ever international military operation, American Marines were sent to take on these tyrants in what were called the Barbary Wars.

It wasn’t easy. They started by trying to blockade important ports in Algiers, Tangier & Tripoli where the pirates had their bases. The first ships sent over were frigates that were too large to go close to shore where the corsairs could go, so the blockades were not highly effective. They tried to bombard them with cannons, which helped to some degree, but real progress was not in the cards until smaller ships joined in the fight. But the final defeat of the corsair plague was the result of an American special op.

Attacks on the fortresses of the seaport were difficult because of the staunch defenses that had been built up. Even when they were able to stop the corsairs from coming and going, they were having trouble taking over the ports themselves. In a wild attempt to get Tripoli to surrender, one of our Naval chiefs, Commodore Edward Preble, decided to nuke the Tripoli port.

An enemy ship had been captured not long before. It was renamed the Intrepid. A huge floating bomb was built by cramming as many explosives into the Intrepid as possible. They would then cruise her into the Tripoli port, disguised as a friendly. The plan was for the Intrepid to be detonated in the port, among the enemy gunboats, and against the fortified walls of the city. Because of the risk of this operation, Commodore Preble only asked for volunteers to steer her into the harbor. A few other small boats were sent in to take the Intrepid crew to safety once the bomb fuse was lit.

This operation did not go as planned. The Tripoli guards sensed foul play and opened fire on the ship before it reached its destination. At 10 in the evening, the Intrepid exploded in the middle of the harbor, taking with it all of her crew, and the crews of the smaller boats accompanying her. None of the commandos survived.

Conditions in the war were not improving when a particular man of questionable character in American history rose briefly to the forefront. By some accounts, William Eaton was a volatile and opportunistic smuggler who used his position in the military to enrich himself. His own CO tried to court-martial him on charges of selling government supplies to the Creek Indians, among other dealings. He was acquitted, but his reputation was besmirched and he was blackballed.

But straight out of a Hollywood movie, Eaton was soon recruited by the Secretary of State to conduct a shadowy operation, an arrest and seizure of documents tying a Senator to a conspiracy with the Brits. It turned out that Senator William Blount was conspiring, and Eaton’s operation proved to be a success. His reputation was restored and he was given a post in Tunisia, one of the hotbeds of corsair treachery.

After the Navy’s failures, Eaton cooked up a plan to overthrow the top dog in Tripoli with an exiled brother. He was given a little cash and 8 marines to see where it would go. He took the 8 marines and turned the ragtag band of brothers into a mercenary army of 400, digging up all kinds of rabble in the slums of Alexandria with the promise of paying them afterward. Not only were they told to sit tight on payment, but they were asked to march 600 miles over the desert to their target, a fortified city called Derna. It was the first time Americans would launch an invasion on foreign soil. Through Eaton’s ingenuity, he kept the hungry, bickering mercenaries from revolting and succeeded in the goal of taking Derna. This turned out to be the straw that broke the camel’s back on the Barbary Coast. The major corsair states signed peace deals and American ships were free to cruise the Mediterranean without risk of being attacked.

Eaton wasn’t satisfied with the terms of the surrender. He thought the Americans should have been more demanding since they had the Barbary states’ jewels in a vice. He recommended a stricter set of demands but they were not agreeable to the powers in Washington. Feeling he had not been given credit for winning the war, Eaton self-combusted not long afterward. He started drinking and he spoke publicly about how he had gotten shafted, blaming high-ranking officials with no filter. His claims were salacious news because he was something of a star, just not as important as he had hoped. But as it happens, when you piss people off in high places, you get canceled. His final days were spent in a downward alcoholic spiral.